Ringboard: the infinitely scalable clipboard manager for Linux

Technical overview of a high-performance multi-arena ring allocator database

Published Jul 21, 2024 • Last updated Sep 22, 2025 • 28 min read

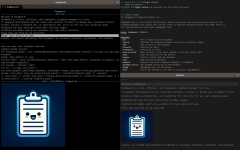

Ringboard TUI on the left, Ringboard CLI and GUI on the right (top and bottom respectively).

Ringboard is a simple yet powerful clipboard manager, designed for Linux to be desktop environment (DE) agnostic. Ringboard strives to be as efficient as possible, use a minimal constant amount of memory, scale to massive clipboards, and be composable with the rest of the ecosystem. It is implemented using a client-server architecture (with a Unix Domain Socket) which enables using a command line interface (CLI) for lower level operations, a terminal user interface (TUI) for a convenient yet unobtrusive interface, and various graphical user interfaces (GUIs). Currently, the clients include a stand-alone GUI implemented using egui and a TUI implemented using ratatui with plans for a COSMIC applet (issue) and Gnome extension (issue). Ringboard aims to be the best clipboard manager for Linux.

- Introduction

- Background

- System architecture

- The server

- Clients

- Advanced features

- Flaws

- Random whining

- Conclusion

Introduction #

Ringboard supports copying arbitrary data—that includes images, PowerPoint slides, or anything else you might conceive of. In fact, Ringboard is a byte-oriented database masquerading as a clipboard manager. The core technology is founded upon the following axioms:

- Data is (mostly) append-only.

- The primary operation is insert.

- Old entries may be deleted transparently.

- There is an arbitrary upper bound on the number of entries.

These axioms lead to the theorem driving Ringboard’s technical decisions: the number of entries stored in Ringboard approaches the maximum entry count as a user uses the clipboard. An important corollary is that insertion also requires deletion with high probability. Therefore, Ringboard is implemented as a disk-backed ring allocator with the freedom to delete old data whenever the allocator runs out of space.

As you will see, Ringboard scales “infinitely” in the sense that we never need to hold the entirety of the database in memory at once, so we are limited only by disk storage space. In practice, Ringboard holds almost none of the database in memory, using just a few hundred KiBs of memory. Only reading the necessary parts of the database makes both client and server startup times extremely fast—less than 50ms in my benchmarks. In brief, Ringboard can effortlessly handle millions of entries.

To be fair, none of this is particularly impressive from the perspective of a database implementer. However, in the world of clipboard managers where data is usually stored as a single JSON/XML file or not at all, this design is comparatively advanced. As noted earlier, there is a key domain specific property Ringboard takes advantage of that makes it more efficient than any general purpose database: data can be deleted transparently.

Background #

Ringboard has ancestral roots in my Gnome Clipboard History (GCH) extension which was implemented as an append-only log. GCH’s log is unfortunately not self-synchronizing as there are back pointers with arbitrary locations, meaning you have to read the entire log and apply operations sequentially in order to accurately reconstruct the database.

Since I was finally able to use Rust for this next generation clipboard manager, I wanted to find a way to use the mmap syscall such that I could both have the entirety of the clipboard database available through memory accesses while also not requiring that data to be held in volatile memory. In other words, Ringboard lives with the illusion that the entire database is in memory while in reality only a few pages’ worth of it are—turns out you can have your cake and eat it too!

The key idea improving upon GCH was to split metadata and data so that each entry’s metadata is a fixed size. This and other insights leading to the final design described in this article are available here.

System architecture #

Ringboard supports two kinds of clipboard entries: normal and favorites. Favorited entries are always visible and should stick around even if we need to start deleting normal entries. Thus, Ringboard is really N ring allocators with a shared backing store. While the full generalization hasn’t been implemented, this architecture enables the possibility of tagging entries (each tag is its own ring). Currently, N=2 is hardcoded to support the normal ring and the favorites ring.

Each ring holds the metadata for its entries. The backing data store is shared between rings and consists of a file per entry for large entries or a slot from an arena allocation for small entries. A diagram will hopefully be easier to understand:

Note that I use the terms arena and bucket to mean the same thing (probably incorrectly).

The ring #

A Ringboard metadata store consists of 4-byte entries arranged in a fixed length ring buffer (resizing is discussed later). If the user doesn’t have the maximum number of entries yet, adding a new entry appends to the metadata file. Once the maximum has been reached, we cycle around and begin overwriting previous entries. Deletions and moves are handled by uninitializing the old entry (skipping over such tombstone entries while reading), and (un)favoriting is handled by moving the entry between metadata rings.

Every ring includes a header with a 3 byte file signature (chosen by a fair dice roll of course), the ring’s version (for future compatibility), and finally the write head (i.e. where the next entry should be written). The ring never shrinks and therefore does not need a tail pointer as the tail is implicitly encoded as the write head (while the head pointer is technically the write head minus one).

Ring entries #

Ring entries are a fixed size because this gives us a critical ability: the UI can perform simple pointer arithmetic with the write head to retrieve the N most recent entries. For example, displaying the last 100 entries requires reading just 400 bytes from disk—that’s a single disk block (or two if you’re unlucky and straddle two blocks). Compared to GCH and all other clipboard implementations I’ve looked at, this is by far the most efficient implementation for showing the N most recent entries. Most other clipboards must read in the entire database on startup, limiting scalability.

An important tradeoff to consider with fixed size entries is precisely the fact that they have a fixed size. Too much space for information and suddenly storing metadata becomes expensive, too little and it is no longer useful. I hope you’ll agree that 4 bytes is fairly space efficient:

- For small entries, the lower 12 bits store the size (in bytes) of the entry while the upper 20 bits store the location of the entry in its size bucket (see the next section for the data store implementation).

- For large entries, the lower 12 bits are all zeros while the upper 20 bits simply need to be non-zero, but are otherwise unused currently.

- Unallocated entries contain all zeros.

In diagram form:

[ 20 bits | 12 bits ]

Bucketed: [ Index in bucket | Entry length ]

Direct file: [ Non zero | All zero ]

Unallocated: [ All zero ]

Note that this encoding imposes a hard limit on the maximum number of representable entries: 220’s worth. While a million entries should be more than enough, the all ones pattern in the upper 20 bits is reserved as an escape hatch to mean “this is an 8 byte entry,” thereby theoretically allowing more than ~1M entries even though such a feature hasn’t been implemented.

The data store #

At the end of the day, the data store is a glorified memory allocator and thus similar tradeoffs apply.

Storing entries contiguously is best for space efficiency, but leaves holes when entries are deleted. Holes could be avoided with generations, but now you must wait a very long time to truly delete an entry or face expensive compaction wherein all following entries must be moved.

Storing one entry per file is convenient but extremely inefficient for small entries due to the overhead of an inode.

Thus, I settled on arena style allocation where entries are bucketed into size classes and allocated from their respective arenas. In expectation, assuming a uniform entry length distribution (this is wrong, but close enough), about 25% of each bucket will be wasted space. The benefit is that holes from deleted entries can be filled in O(1) time. Was this the right choice? Probably? I still wonder if generations would have been better.

Specifically, there are 11 size classes in powers of two from 4 to 4096. Entries larger than that are stored in a file named by the composite ID of the entry (its ring ID and position in the ring). Any entry with a non-plaintext mime type is also stored in a file regardless of its size due to there being no metadata storage for bucket allocations. File mime types are stored in extended file attributes (which should be stored in the inode itself when small).

Entries 4096 bytes or larger are allocated as one file per entry to avoid paying the 25% wasted space tax—they pay the O(1) inode plus directory entry cost instead.

Ring entries point to either a bucket allocation (implicitly choosing a size class via the entry size) or a direct file allocation. Moving an entry either does nothing in the case of bucket allocations or renames the direct file for direct allocations. Deleting an entry simply marks a slot in the arena as being free or deletes the direct allocation file.

Directory structure #

~/.local/share/clipboard-history/

├── buckets

│ ├── (0, 4]

│ ├── (4, 8]

│ ├── ...

│ ├── (1024, 2048]

│ └── (2048, 4096)

├── direct

│ ├── ...

│ └── 0004294985353

├── main.ring

├── favorites.ring

├── free-lists

└── server.lock

The server #

The server’s only job is to handle writes to the database. In fact, the server is the only process ever allowed to modify the database. However, it does not decide what to write down and therefore sits around waiting for commands from clients. A client could be a Wayland or X11 clipboard listener for example which will inform us when the user has copied something. Clients can also be GUIs that wish to modify the database or get notified of changes.

The server is implemented as a single-threaded event loop using io_uring.

Protocol #

Importantly for performance, the server never sends data to clients. Instead, clients use a library for interfacing with the database in a read-only manner, thereby avoiding any bottlenecks in the server. Currently, clients don’t react to changes in the database, but there are plans to keep clients up-to-date by having the server broadcast change details as they occur. For rare commands that change a large portion of the database (like garbage collection), clients would be told to reload the entire database. In practice, the primary flow would consist of a user copying something, the server getting notified via a client, and finally broadcasting the event to subscribed clients. Notice that if a client does not subscribe to updates or make modifications, it need not even connect to the server.

The command protocol consists simply of the in-memory representation of the command structs. To maintain forward compatibility, the client and server exchange protocol versions with each other and reject the connection if they do not match. This avoids issues when a client is running a newer binary than the server or vice versa. Perhaps in the future there may be a case for supporting backward compatibility, but for the moment the client and server must be built with strictly the same protocol.

Recovering from unexpected shutdowns #

To avoid wasting disk writes, the server keeps the list of free arena slots in-memory and (de)serializes them only on startup/shutdown. The free slots only being up-to-date in memory means that if you lose power while Ringboard is running, we’ll have no idea which slots are free.

A lock file is therefore used to detect unclean shutdowns: it is created when the server is started and explicitly deleted when the server is shut down through the happy path. Thus, any unexpected halt can be detected by the presence of the lock file. As a bonus, the lock file is also used to prevent multiple server instances from running concurrently.

If an unclean shutdown is detected on startup, the server will stream through every ring, building an allocation bitset to compute free bucket slot indices.

Note that there is no recovery from corruption due to failure while writing entries, but any potential corruption is localized. This is discussed later.

Rings, rings everywhere #

Io_uring—barring a few hiccups early on—has been a pleasure to work with. It made writing an efficient single-threaded server a breeze. To illustrate, consider signal handling: using signalfd, we can post a read request to io_uring and handle graceful shutdown alongside the rest of the event loop. No need for blocking code, threads, or pipes to handle signals! The server’s simplicity is driven by the ability to write a clean event loop.

io_uring’s bounded nature enables the server’s low memory usage. Queues and buffers have a fixed size, meaning io_uring code can rely on a known capacity for external inputs. If clients overload the server, io_uring simply fails the request. This leads to natural backpressure, where (for example) if clients don’t reap replies fast enough, their send budget will be reduced.

A note on mmap semantics #

Memory mapped file coherence is simply delightful on Linux. Barring wonky CPU architectures, file modifications through syscalls like write will be reflected in the file mapped memory of any process. This is important because it allows us to mmap more memory than exists in the file! In fact, the ring mmaps enough space to hold the maximum number entries, even though the ring on disk may be completely empty.

The coherence between virtual memory and files enables us to avoid remapping the ring whenever it grows—we use standard write syscalls to write past the end of the ring and those changes are then reflected in the mapped memory. More precisely , if user space touches a page that does not have any backing bytes in the file, the program will segfault. However, if a non-zero number of bytes map to the page, then the entirety of the page becomes valid and the slices which contain no backing data are filled with zeros.

But why not write to the mapped memory directly? Setting aside the performance loss of extra page faults, Linux offers no guarantees on when newly written data is made visible to the file system. Importantly, this means there are no ordering guarantees between writes which is unacceptable for database reliability.

Clients #

Ringboard was originally intended to be a single application, but I quickly realized that it would be useful to support many different readers and writers at once. To make reading the database fast, clients need only interact with the server when they wish to modify data. Clients connect to the server via a socket if necessary or use a client SDK to read data from the database. This approach allows some clients to avoid ever connecting to the server as they only need to read data. Supporting multiple clients also means it is easy to allow saving clipboard entries from X11 or Wayland or a CLI etc. Similarly, any number of interfaces to the database can be built for different use cases from GUIs to JSON exports.

Receiving copied items via Wayland or X11 #

Since Ringboard follows a client server architecture, the server knows nothing about the clipboard—it is simply a data store. This keeps the server focused, simple, and flexible. Clipboard monitoring is instead performed in a small binary whose only task is to listen for clipboard changes and send new entries to the server.

An aside on the nature of clipboards: which mime type to use? #

When you copy something, what format is the data in? You might think there is a canonical format for copied data, but far from it. Consider something as simple as copying this very sentence. What did you just copy? Plain text or HTML? The answer is both, depending on the context. If you paste into a word processor, it will try to match the format of whatever you’ve copied and will therefore ask for HTML. But if you Ctrl + Shift + V, you’re asking the word processor to paste in plain text so that’s what it will ask for. Fun fact: this is why the code copied from your favorite editor comes with that sweet sweet theme styling you worked so hard on. Try it! Copy code from your editor, then check the available data formats with xclip -o -target TARGETS -selection clipboard. You should see text/html in there. Now ask for that HTML with xclip -o -target text/html -selection clipboard and open it in a browser. Lookin’ good. 😎

The problem for a clipboard manager is that applications holding clipboard data are free to perform on-the-fly conversions. For example, Firefox offers a PNG, JPEG, AVIF, HTML, and other formats after copying an image. Supposing the clipboard could correctly save all the formats available, it would end up with many undesirable duplicate copies of the same entry. Unfortunately, retrieving all formats cannot even be done correctly as the owner of the clipboard data is free to do anything they like, such as returning different data each time you ask for it or performing lossy conversions (for example, copying an SVG in Chrome or Firefox doesn’t let you ask for the SVG and instead only offers a PNG conversion). Asking for copied items in every available format to try and capture the underlying data therefore isn’t practical or possible.

In fact, the system clipboard faces these same issues. When an application which owns the clipboard is closed, there is suddenly no way to ask it for the clipboard data. Thus, the compositor must store some version of the clipboard contents in memory so what you’ve copied doesn’t disappear after you close the application it was copied from. This process is lossy. It’s why pasting something from a closed application can behave differently than when it is open.

Here are some further examples I used to convince myself I was on the right path:

- When copying something from a web page, it is quite rare to want the HTML version of the text.

- The same logic applies to copied code: the vast majority of the time, you’re working and not trying to paste a pretty version in a slide deck. No point in remembering the pretty version forever.

- When copying files in a file manager, you sometimes want the path and sometimes want to copy the file. For cases like this, the file object can be stored as the canonical representation and offered as a path by a conversion in our code.

- The same applies to images: we can store a JXL for example and offer to convert it to a PNG.

Finally, it’s worth remembering that Ringboard is a byte oriented database. If it turns out we need to store multiple mime types for some specific use case, we could store an entry with a special mime type (say

x-special/ringboard-multi) containing a serialized object that describes each representation of the entry. The various clients will need code to handle this special mime type, not unlike how they have special code to handleimage/*mime types.

So what can we do? We guess, unfortunately. That means trying to pick the “best” format available to save (which as a reminder isn’t possible because the right format is dependent on the paste context). We use heuristics: for example, if an image is available we’ll pick the first mime type starting with “image/”. For anything not in our heuristics, we default to picking plain text. As a consequence, we need your help to improve these heuristics so they can handle your wonky mime type of choice. :)

Pasting items #

As mentioned above, the clipboard operates on a pull model: when someone wishes to paste, the current program asks whichever program owns the clipboard for its contents. This means that the clipboard owner must live at least long enough for the compositor to make a copy of the clipboard contents, and must live indefinitely if the program wishes to provide a full pasting experience with multiple mime types.

Thus, another server was needed to own the clipboard for a Ringboard entry, thereby reconciling the contradictory short-lived nature of a client and long-lived nature of a pasting program. Since the clipboard watcher already talks to the clipboard and is a long-lived daemon, the paste server was added alongside it.

The paste server is implemented with a simple epoll multiplexing mechanism over a connection-less Unix socket.

GUI startup latency and long-lived client windows #

Initializing a GUI can be quite slow (especially in X11): on the order of a few hundred milliseconds. Since this brief pause in someone’s train of thought while trying to paste a previous clipboard entry would be extremely annoying, GUI clients make their windows invisible when closed rather than completely quitting. To reopen the window, a special file can be deleted which wakes the GUI via inotify. If, instead, a new instance of the GUI is opened, this special file is used to first check for a previously running instance of the GUI and kill it if it exists.

Advanced features #

Search #

Search is always tricky in settings like these. A full-blown index feels wasteful to maintain and store for such little data (even 100K entries at an average of 100 bytes is only 10MB), but scanning through the whole database is also ugly. Still, I went with the ugly approach for its minimal overhead in the server.

Thanks to our arenas, it is easy to parallelize search in an optimal way for the hardware. Each arena is linearly searched on its own thread which means we are performing a (mostly) linear scan of the data. The rings are not involved at all. As a consequence, we will search through deleted entries and don’t know how long each entry is. If a result is found in a deleted entry, we simply ignore it later. As for knowing the length of each entry, the server places a NUL byte at the end of each entry for search to stop at. Note that search therefore does not work properly on entries which contain NUL bytes as data.

On another thread, the directory of direct allocation files is scanned and each file is searched when its mime type suggests the file contains text. Currently, no additional parallelism is used, but large files could be searched on their own threads to avoid bottlenecking on direct allocation search.

Finally, applications will likely want to know the entry which owns the search result. To do so, they build a reverse mapping of bucket slots to entry IDs by scanning through every ring. Thankfully, this mapping can be computed in parallel to the search and reused across searches, so is not too expensive. Furthermore, if applications do not need the entry ID for something (for example they only wish to copy the data somewhere), then there is no need to build this reverse mapping.

Garbage collection #

Since deleting bucket entries can leave holes anywhere in the relevant arena, we end up with garbage bucket slots which hurt search performance and waste space. There is also garbage in the form of tombstone entries in the ring, but their numbers are bounded and they are guaranteed to be reused, so we do not worry about them.

To determine when to remove dead bucket slots, we have several policies to choose from:

- Do nothing. Under a continuous random process of adding and removing entries, all garbage will eventually be reused. Unfortunately, this process also leads to eventually infinite garbage.

- Always remove the garbage immediately. This wastes a lot of work and disk I/O when new entries could have reused an arena slot that was freed not too long ago.

- Remove garbage on a schedule, for example when the server starts up and every N days thereafter. I’m not a fan of startup latency. Additionally, this policy allows garbage to grow unbounded between collections.

- Remove garbage immediately when it’s created, but only if the total amount of garbage exceeds a threshold.

I chose the last option because it guarantees an upper bound on the maximum amount of garbage and keeps a small amount of useful garbage around. Specifically, when a GC occurs we only remove enough garbage to put ourselves under the maximum amount threshold (plus a little more to avoid excessive collections), inhibiting a big sawtooth pattern that would occur if all garbage was removed when the threshold is exceeded. This makes the removal process more complicated because we must now choose which garbage to remove. Since we expect bucket allocation sizes to follow some distribution (copying lots of words/phrases is more common than whole paragraphs for example), freed bucket slots will therefore also match that distribution (though a distribution change will take time to propagate). Thus, we can expect the number of free slots per size class to be approximately uniform as the alloc and free distributions pair off. This means we should uniformly remove garbage from each size class, one layer at a time.

To minimize disk I/O when removing garbage, we fill unallocated/garbage bucket slots with allocated entries from the end of the arena. Once we only have (newly) unallocated slots at the end of an arena, we truncate the arena file to drop those dead slots. To further encourage usage of free slots near the beginning of the arena, we sort the free lists so that earlier slots are filled first.

A client pass is also available that first deduplicates the entire database before running garbage collection for extra space savings. This works by computing a hash of every single entry and when two hashes collide, checking to see if the contents of the two entries match, deleting the oldest entry if so.

Ring resizing #

Currently, the maximum number of entries is hardcoded, but there are plans to support changing this default after the database has been created.

Flaws #

Blocking reads #

Io_uring doesn’t support the copy_file_range syscall which means we can’t copy client data asynchronously using io_uring. Even if copy_file_range was supported, as a practical matter, manually writing a coroutine to make all syscalls on the database write path async would be intractable. Thus, database modifications block the entire server, meaning one client can DoS the server. This is easy to reproduce by writing some code that asks the server to write an entry whose contents is stdin—the server will be frozen until stdin is closed.

I don’t believe this is a problem since we assume that clients are cooperative (see below) and therefore assume they will provide the server with a non-blocking file. However, if some unforeseen circumstances change the equation, then there is a relatively straightforward solution: move the allocator to a background thread and communicate with it using SPSC channels. The background thread would write into a pipe whenever it has sent a message so that io_uring can wake up and process allocator responses. However, keeping track of pending requests and applying backpressure would be complicated, hence why this approach wasn’t chosen.

Database reliability #

Both of these issues should be extremely rare (if not impossible) to hit under normal circumstances. Nevertheless, their possibility sucks and is sad to think about.

Local corruption #

On disk, the one rule offering some saving grace is that the database as a whole may never be corrupted. This is an improvement over Gnome Clipboard History which could be destroyed by a single bad bit, but it still means that Ringboard is susceptible to local corruption. Metadata being a fixed size means a corrupted entry does not affect the others, but by separating metadata from data we introduce a race between changing the data and the metadata. For example, crashing before the data has been flushed to disk but after the metadata has flushed will lead to corruption when adding an entry.

This could be easily fixed with an fsync, but there are more complicated cases that can’t be solved without journaling: if a non-bucket entry is deleted, its file and ring entry must be deallocated, but there is no order in which these operations can be performed without corruption of some form given a crash between the two operations. If the metadata is removed first and we crash, we’ll forget that we need to delete the data file; if the data is deleted first, then the metadata will end up pointing to the void.

Thus, I decided that local ring corruption was acceptable given the enhanced efficiency of not using a journal.

Raciness #

The project’s biggest shortcoming is caused by clients being able to independently read the database while it is being modified, leading to inherent race conditions.

In memory, clients do not have any control over writes the server executes, meaning a client could be using a buffer the server deallocates. For intended use cases (like garbage collection), this can be solved by notifying clients to reload the database, but there could be awkward situations where, for example, a client is looking at an old search result that gets overwritten by a new entry. While clients should watch for such changes, the possibility for nonsensical memory reads remains.

This case could be solved by having clients ask the server to lock ring ranges or by having the server ask clients for permission to modify ring entries (two-phase commit), but I decided that the complexity and overhead was unnecessary for a clipboard manager. As a reminder, clients can never modify data and therefore memory errors are transient which makes them slightly more acceptable.

Error handling and malicious actors #

In general, the Ringboard server takes the view that clients are good citizens and try to share resources amongst each other. This unfortunately means that the server doesn’t try particularly hard (if at all in many cases) to recover from runtime errors. If something goes wrong, the server will simply shut down with an error message (to be clear, the server should never crash, but it is allowed to die).

I went with minimal error recovery for two reasons. First, clients want to be good citizens. A user is installing clients on their own machine—why install a client that will shoot them in the foot? Second, error recovery is hard. You are writing code that will almost never be executed and probably requires a convoluted set of conditions to be met before firing. For a clipboard manager, I would rather have maintainable code that almost never fails but may need to reboot if things are broken than code which must gracefully recover from every I/O error.

Complexity #

At the end of the day, Ringboard is a very complicated project with a lot of moving pieces and a simple sounding goal: remember stuff you’ve copied. Thus, the question must be asked: is this complexity worth it? I believe the answer is yes. Simple projects get the job done, but sooner or later, they end up wanting more functionality and better performance. Without the discipline to accept their limitations, these projects are inevitably rewritten as they grow organically. I prefer the philosophy of writing things once and getting them right the first time. If “right” still comes with compromises as is almost always the case, then those compromises must be accepted and core functionality changes rejected in order to maintain the original vision. Core changes are what v2 projects are for—in other words, Ringboard is Gnome Clipboard History’s v2.

Random whining #

Writing fast and maintainable code is still stinkin’ impossible #

To get a sense for what I mean, consider an API for a case-insensitive plaintext search API. The maintainable version might look something like this:

fn search(query: &str) -> Results {

do_stuff(&query.to_ascii_lowercase().trim())

}

The problem is that to_ascii_lowercase allocates a String on the heap and all you need at the end of the day is an &str. You look at your call sites and see that they all already have a String, so you decide to reuse it:

fn search(query: &mut String) -> Results {

query.make_lowercase_ascii();

do_stuff(query.trim())

}

But now you want to trim the query in some places but not others… well too bad because .trim() returns an &str (as an in-place trim would have to move all the bytes over), so you’re back to needing an extra allocation, at the call site this time: search(query.trim().to_string()). The only way to remove the extra allocation is to bleed your requirements across function boundaries:

query.make_lowercase_ascii();

search(query.trim());

// …

fn search(query: &str) -> Results {

debug_assert!(query.is_ascii_lowercase());

do_stuff(query)

}

This pattern where a caller already has a costly object ready that can’t easily be used in the maintainable API shows up all the time in low-level code. I feel like this might be fundamentally unsolvable as the API needs to know call site implementation details to be fast. Perhaps specialization could help, but I haven’t thought deeply about it.

Error handling still sucks, especially in GUIs #

I’m tired of writing map_err every two seconds to provide context on why an error occurred. And no, being lazy and just returning the io::Error as is so you get a File not found error with no file path to tell you where the error came from is not acceptable. In GUIs, the story gets even more annoying: not only does any external action need to handle errors, but you then need a dedicated place in the GUI to display those errors so the app doesn’t just silently do nothing. Testing it is a nightmare because the errors never happen in practice so you have to temporarily comment out the working code to return fake errors. Sometimes I wonder if .expecting everything might be the way to go.

Writing GUIs that spark joy is a pain, especially in Rust #

Until our Lord and Savior Raph Levien blesses us all with glorious Rust GUI, simpletons like me live in existential agony desperately trying to smooth out a stuttering, buggy mess of a GUI that looks like it came from an engineer’s nightmarish disdain for any form over function. I hate GUIs. So much.

egui in particular just isn’t ready for real-world UIs: achieving desired behavior is buggy and finicky. Then again, I would say the same thing about Android development and HTML/CSS so perhaps all UI is cursed.

Conclusion #

Hopefully this overview of Ringboard provides adequate insights into its inner workings and the reasoning behind its design choices. In a perfect world, Ringboard’s design is flexible enough to support self-sustaining communities around each client implementation.

Happy copying!